|

The world of non-commercial film and A-V |

Events Diary | Search | ||

| The Film and Video Institute | | ||||

The making of 225 - by Christopher David

Introduction: The Gears | From Ideas to Footages | Post-production: Tricks revealed |

Post-production

Space (and my typing) doesn’t allow for me to detail every shot. Of the 150 shots in the finished film, 105 include computer special effects. Here are just three:

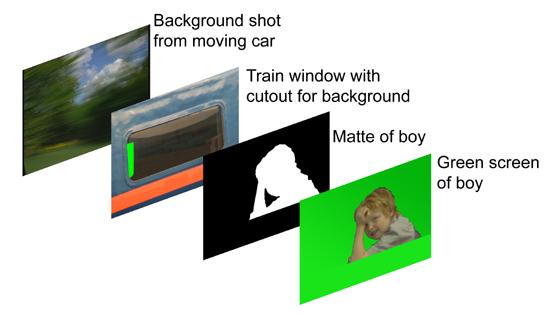

View into carriage from alongside

Having decided that a real tracking, or crabbing, shot alongside a 150mph train was almost impossible to achieve, I set about creating one on computer.

The actual carriage was created from digital stills taken from the opposite platform at a railway station. (Careful note was taken of position of sun, angle of camera from perpendicular etc). Back home the pictures were retouched, tell-tale reflections airbrushed out and track and backgrounds removed. Holes were cut at the windows to show the moving backgrounds (shot previously from a car window).

Elsewhere, Roo was filmed against a green screen, (again paying attention to a matching lights and camera angles), and was given directions, descriptions and sightlines of what he would eventually be ‘seeing’.

A section of track was photographed and used as a basis for a computer model approximately 1000 metres long. The model was twisted to match the perspective of the still pictures. Once moving, and with blur added, the results started to look quite convincing!

Bushes, trees and catenary pylons were added - whooshing past in the foreground, and reflections inserted to the (non-existent) windowpane.

Finally, camera-shake was added.

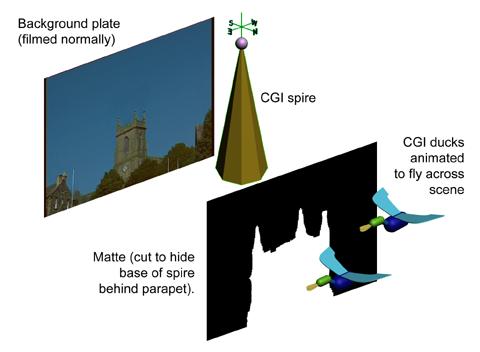

Church Spire

You may be surprised to know that no churches were harmed during the making if this film! A suitable church was discovered, it having a tower and no spire.

The sequence had already been (vaguely) story-boarded, so the camera was set up to capture the backgrounds. Care had to be taken to frame the shots to allow for the (non-existent) spire, and for the movement and flight of the spacecraft.

Back home a church spire was built on computer. MAX allows us to add materials and texture to any object, in this case – granite. The spire consists of 217 individual granite blocks, along with a weathervane. Special care had to be taken to match the texture and tonality of the CGI stone with the real building. Detailed pictures were taken of the churches stone and Photoshop was used to ‘tweak’ these images to apply them to the CGI spire.

The spire was then aligned with the background plate. This proved quite difficult because of the extreme perspective views looking up the tower. Special masks were created where the real church’s architecture interfered with the CGI spire. To complete the illusion of ‘oneness’ a pair of CGI ducks fly across, helping to embed the spire into the scene. Their distant ‘quacking’ also creates a moment of English pastoral tranquillity- which serves to heighten the mayhem to follow.

After the impact every individual block was programmed with a fall pattern – its spin and trajectory, to create the random effect of impact and explosion. “Particle Sprays” were used to create clouds of smoke, dust and debris, and to control the direction of the showers onto the camera.

Girder Bridge

Many people have asked me about this sequence, and whether I work for the railway company. Apparently this is because the ‘crane’ shot looks quite convincing, and could be achieved no other way!

There is no crane. There is no girder bridge.

Watch the film closely and you can see we use the same trackside shot – but this time with a digital bridge added. (Perspective is important here).

I photographed and studied a real girder bridge before starting the model. Some of these photographic details – rust, flaking paint etc - were later incorporated for authenticity into the digital model. An “invisible” CGI matte ‘ground’ was used to accept the shadow cast from a CGI light positioned to replicate the sunlight.

The crane shot is an optical illusion. (Notice, as you walk along, how objects far away appear stationary. The moon, or hills in the distance, don’t seem to be getting any closer, despite the fact you’re walking towards them!)

Our shot shows the camera craning down through the CGI lattice steel-work

of a girder bridge, but the background (real train on real track passing under

real bridge) remains stationary throughout.

For the technically minded, I used ‘Blinn’, ‘Metal’,

and ‘Oren-Nayar-Blinn’ shaders as appropriate. All these images

were rendered using a mixture of “Catmull-rom” and “video”

filters using a native WSD Digital recorder. The files were ‘anti-aliased’

and image blur was added at this stage. I did not use a codec. Every shot

was rendered ‘uncompressed’ – leading to some massive file

sizes. In fact, I have a box of over 70 CD-ROMS containing every CGI shot

from the film.

Motion blur was added on completion of each shot. As well as adding authenticity it really does help to hide many errors in the compositing process.

Audio

I’m surprised at how often we neglect sound quality. Whilst we’ll strive for (and achieve) digital picture perfection, all too often our soundtracks are relegated to an uninteresting, hissy, mush. I’ll risk controversy and say NO camera mic is any good. Period. (But that’s another article).

For “225” I felt it is important to place the mic to get the best subject sound. Consequently, every sound was re-recorded and dubbed in post-production. Voices were recorded in a quiet room at home. Rustling paper and pencils- the same. Train interiors were recorded on a separate journey. Passing trains (exteriors) were recorded at the trackside at night (less ambient noise). Other atmospheres and details were taken from sound effects CDs.

The final explosion, where the craft disintegrates alongside the train used 18 channels of audio. I wanted this element to be powerful and LOUD, so when mastering the final mix, a lot of time and attention was spent taking this section to the absolute limit of the digital ‘headroom’, whilst still keeping it ‘legal’. To contrast this and create the “calm before the storm” some of the birdsong at the start of the film is barely audible.

Conclusions

Virtually every evening for twelve months was spent creating the film. It was worth it, and the film has been very well received both in the UK and overseas. There are things I would change, and ideas that – with hindsight – could have been executed better. It shows that ‘virtual’ or computer filmmaking is not the province only of Hollywood. In fact much of the software serves to level the playing field, bringing big budget spectacle within the reach of the home movie-maker.

We amateurs have a lot going for us! Providing we maintain a flame of enthusiasm, and show the same creativity as our professional counterparts (not that difficult, sometimes) we can now deliver results that once we only dreamed of.

And just like Hollywood, a sequel to 225 is in the pipeline!

Introduction: The Gears | From Ideas to Footages | Post-production: Tricks revealed |

Share your passions.

Share your stories.