The making of Until the Day Breaks

To BIAFF 2016 results| To Full Making Of Index

Anna and Paul Kittel won 5 stars and a sponsor's award at BIAFF2016

One Friday evening our nine-year-old son, Peter, came home from school with a note. The school was commemorating the hundredth anniversary of the First World War and the children's homework was to gather as many pictures and facts as they could about life between 1914 and 1918.

As Peter typed 'WW1' into the search engine of the family computer, Anna told him that two of his Great-Great-Great Uncles fought in the First World War. Their names were Alfred and Bert Stittle. Anna said that she didn't know much about them but as we were due to see Granny and Granddad in the next few days, perhaps Peter could ask them.

I suppose it was at this stage that the germ of an idea about making a film was sewn. Anna and I love making family films with our children Peter and Freya. The films involve the whole family and, in the process, it's great to learn something about ourselves and our history. We've previously made films about my dad's exploits as an amateur film-maker and another celebrating my mum's 70th birthday. A hundred-year-old story about two war heroes would be a very different proposition.

The main problem was that we were short of pictures. All we had was a couple of photos of Alfred and Bert in uniform and some other old family stills. They certainly weren't enough to form the basis of a documentary. The other challenge was to make the audience care. Alfred and Bert's stories, however fascinating to our family, did not appear unique. Huge numbers of people died in the First World War, so what could we do to make their stories special?

The answer to both problems was to create a narrative around Anna, Peter and Freya as they learned about their brave ancestors. Hearing the soldiers' stories in the present tense, through the prism of the family, would allow the audience to share their emotions as they make their discoveries. Emotion is a vital ingredient to all films. Without it, all we'd be presenting would be a heap of dry facts that was unlikely to engage an audience.

We headed to Eastbourne a few days after Peter had been given his school assignment. Anna's parents had kindly arranged for us to join them at the Grand Hotel for a luxury weekend. I didn't want to be encumbered with a lot of camera equipment on a family weekend, so I made the decision to shoot everything on a Canon 60D. This would be my first venture filming solely on a DSLR. I bolted a heavily wind-gagged portable 4-track on top for sound and hoped for the best. My rig may have been fiddly and inelegant but it was small and portable.

The weekend was a predictably drizzly affair and we spent more time than anticipated indoors. On one of these occasions, we filmed the first sequence of our film. I like films to have a driving narrative, which means they shouldn’t be trapped in the past. Even when the primary material is historical, events should, where possible, unfold on screen in the present tense with at least one important fact delivered in each scene. This is what I hoped would give our film dynamism.

Anna's father had brought a sealed envelope, which he opened on camera while the children watched. Everything had to be shot in real time to ensure the children’s reactions were genuine. The most interesting image in the envelope was a Victorian photograph of the Stittle family. It was one of those wonderful starchy photos that were very much of the era: a bearded patriarch and his large family staring into the lens of a, no doubt, blanketed camera. Alfred was a young boy in the picture and Bert was a babe in arms. Peter, who can be surprisingly eloquent for a nine-year-old, asked Granddad a few questions about Alf and Bert. He would ask many more in the coming weeks.

Shortly after our Eastbourne trip, the children broke up for the May half-term holiday. For the past few years we have visited a holiday park in Belgium. This year would be no different but we'd make a detour on the way. Alfred Stittle, the older brother, died in June 1915 near Calais. His grave is in a military cemetery in a small village called Choques. This presented another opportunity for a live sequence.

Like before, I wanted our cemetery visit to unravel on screen so I

filmed our journey and arrival. I anticipated filming a sequence

in which Anna, Peter and Freya searched through the hundreds of graves

to find Alfred's headstone. However as soon as we parked the car, Peter

ran ahead and, as if possessed of some psychic power, ran straight to

Alfred's headstone.

'I've found it. I've found Alfred's grave', he called. It was an

extraordinarily quick discovery.

As the children placed pictures and poppies by the grave, Anna noticed

the epitaph. The inscription read Until the Day Breaks. She

appeared quite overcome with emotion.

The phrase is a biblical quote from the Book of Hebrews and clearly

meant a lot to the brothers' contemporary family. Bert's headstone,

which is in another part of France, is inscribed with the same words.

Until the day breaks and the shadows flee, turn my beloved, and be like a gazelle or like a young stag on the rugged hills.

The full quote is a poignant reminder just how young the brothers were and how much potential had been lost through their deaths.

At this early stage, we decided two things. Firstly, the cemetery scene had to be our film's conclusion. The second decision was to name the film Until the Day Breaks. Like the brothers' gravestones, in a small way this film would also be Alfred and Bert's epitaph.

So our little film had opening and closing scenes. The challenge

would be to create a narrative that would take the audience on a

factual and emotional journey from Eastbourne to France, leaving

them with an interest in Alfred and Bert in the process.

Another filming opportunity arose on the same day that we had visited

the graves. A short drive into Belgium would take us to Sanctuary Wood,

a remarkably well preserved section of trench in the heart of Ypres,

one of the Great War's bloodiest theatres.

The ground was pot-marked with rain-filled craters. Muddy trenches

lay frozen in time, encased in rusty corrugated iron and trees rustled

eerily in the wind overhead. It was as if the ghosts of cold and

terrified soldiers still stalked the wood.

The children were enthralled, running through the trenches and trying

to imagine what life may have been like during a bombardment. Peter

was particularly animated, asking if Alfred had actually been there.

We don't know if Alfred or Bert served in Ypres but we know from

contemporary accounts and letters that they would have been to similar

places. In a way the answer to his question didn't matter. Sanctuary

Wood gave us all a flavour of the war and the type of environment the

Stittle brothers and thousands of others had to endure.

Belgium and France had given the film the 'action sequences'. We

now had the harder task of telling the story.

The truth is, we knew very little. Our position wasn't helped by the events of 1940 when a German bomb hit Whitehall, destroying (among other things) Alfred and Bert's military records. We had to rediscover Alfred and Bert's stories ourselves and had three main sources to call upon. The first was family. Anna's father introduced us to his second cousin Joan. Joan’s late father Harry had been Alfred and Bert’s middle brother. Harry wasn’t called up in time to serve in the war but he saved the letters his brothers had sent to him from the front.

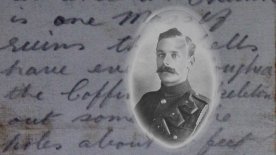

Anna and I visited Joan one Sunday morning. We'd been told that despite

her 94 years, she was still very sharp and keen to remember her uncles

on film. She didn't disappoint. Not only did she have the originals

of the letters but she had more photographs, including a wonderful

portrait of Alfred resplendent with a large military moustache. Each

of the letters were gems, carefully preserved despite the wafer

thin paper on which they had been written. The words gave wonderful

impressions of Alfred and Bert's characters. Bert, who was in his

mid-twenties when he signed up, came across as a fun loving lad who

enjoyed a laugh and a few ales. However, it didn't take much to read

between the lines of his jocular prose to share his disappointment

that active service had forced him to miss his brother's wedding to

Joan's mother. In one corner of the page, he had even written a note

of thanks for a slice of wedding cake that had been sent to him. I

have a mental image of him eating the cake in a muddy trench with artillery

shells flying over his head.

Alfred, who was six years older, wrote in soberer tones. In one letter

he described a bombardment and how it ploughed up dead bodies in a

churchyard. Dark stuff.

Another letter in particular caught our eye. In the fog of war, a

rumour had spread in Alf's home town that he'd been wounded. In

stoical fashion he dispelled this rumour by assuring his family that

he was ‘in the best of health'. The brutal irony was that scarcely

two months later he would be dead.

Another valuable help was an historian called Charles Warner, who

lived in the Stittle brothers' hometown of Soham. We met Charles

after emailing a website called Soham Remembers, which was commemorating

the town’s soldiers that had served in the war.

Charles had done much of the research and knew of Alfred and Bert. We

spent a day driving around Soham with Charles, being taken to various

places that were significant to our story. One place was the Stittles'

family home, which doubled up as a post office and Alf's saddlery.

Joan had given us a photo of the house taken in 1902 so it was interesting

to see how the house had changed in the intervening 113 years.

Our final source of research was the British Newspaper Archive. Local

newspapers from Cambridgeshire had just gone online and we found a

number of contemporary articles mentioning Alf and Bert. It was here

that we learned about Alf's passion for billiards. There was also a

lengthy article about a letter Bert had written to a local publican.

Bert's missive was full of detail and could have made a film in itself

but the only morsel we could feature in our structure was an encounter

he had had with a couple of German biplanes.

These newspaper articles may have been interesting to read but they

wouldn't translate to film without some thought. Like everything else,

they needed to be pushed into the present. I isolated each newspaper

article and saved them on a computer for Anna to read for the first

time as the camera rolled, ensuring a genuine response. The article

that affected her most was the one which quoted the fateful letter

Alf's mother received informing her of his death.

Anna's tearful response may have been for a long lost relative but I believe she was also thinking of our children. How would she feel if they were killed in a war? It's a powerful thought. In the carnage of conflict, it is easy to see the number of dead as mere statistics but behind each death lies a unique story. Alfred and Bert’s are just two tales but I hope theirs will touch anyone who loves their family.

Paul Kittel